To me the figure of Federico García Lorca evokes such different images. Poems of gypsies and slow paced stories about life in the pueblo, to be acted out on stage, are mixed with passionate heartache, outspoken socialist views and a poignant and mysterious tragedy. To this day no one knows for sure exactly what happened to the young Lorca, but it is widely agreed that he was shot by Franco’s nationalist militia at the start the Spanish Civil War. His body has never been found.

Then I realized I had been murdered.

They looked for me in cafes, cemeteries and churches…

But they did not find me.

They never found me?

No. They never found me.

(From ‘The Fable And Round of the Three Friends’, an oddly prophetic poem).

Growing up, the plays of Lorca featured heavily on our Spanish Literature syllabus, especially the ‘rural plays’ – Yerma, Bodas de Sangre (Blood Weddings) and La Casa de Bernarda Alba (The House of Bernarda Alba). While I was recently in Granada with my family, we decided to visit the famous and elegant summer home of Lorca – La Huerta de San Vicente – and from there ended up wandering further and further down the back roads of Andalucia as we were drawn deeper into Lorca’s past.

La Huerta de San Vicente

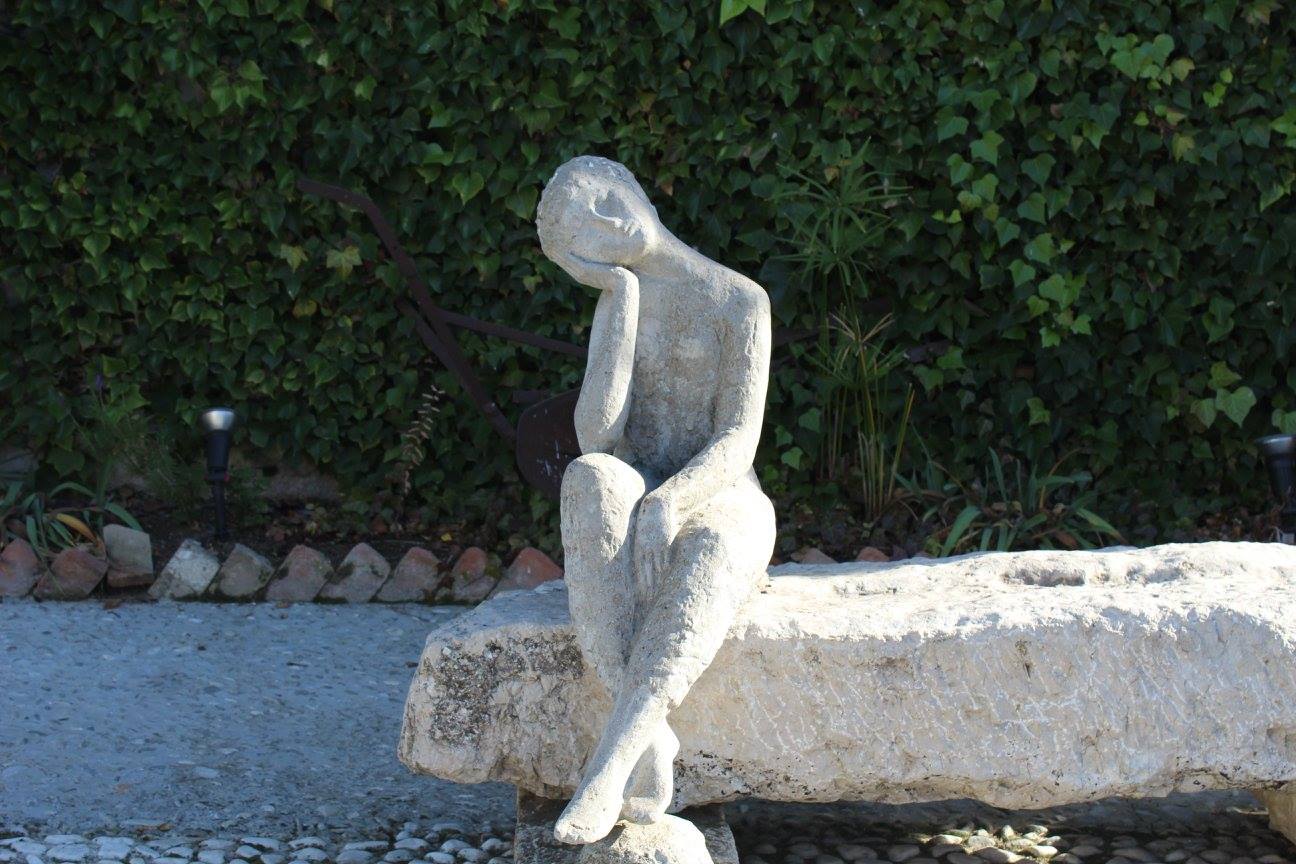

The Huerta de San Vicente, on the outskirts of Granada, is the most famous of the many Lorca houses. Once upon a time he would have been able to visit this charming summer home, sit at his desk and gaze out of the window at the snow covered Sierra Nevada. Today the view from the window is of blocks of concrete flats yet the house remains a peaceful oasis of calm within a bustling city. The white walls are draped with curtains of sweet smelling jasmine and orange trees line the courtyard outside, it’s without a doubt a writer’s paradise. The little garden house was used by the family from 1926 to 1936, after the death of Federico. In his later years, as he spent time in Madrid and in the city of Granada, the summer garden-house became an escape, a retreat where he could reconnect with nature, the landscape of his childhood, his family and the simplicity of the campo. Though, from the letters he wrote to his friends while staying at the Huerta, it does seem that he still managed to find distractions and annoyances, even in paradise!

‘I cannot write. I am nervous, beneath a splendid fig tree, in the thick of the countryside, and struggling with this stupid pencil. Here in Granada I entertain myself lately with delicious things. There is a little bullfighter…’

‘There are so many jasmines in the garden and so many night jasmines that in the early morning they give all of us in the house an almost lyrical headache.’

Fuentevaqueros

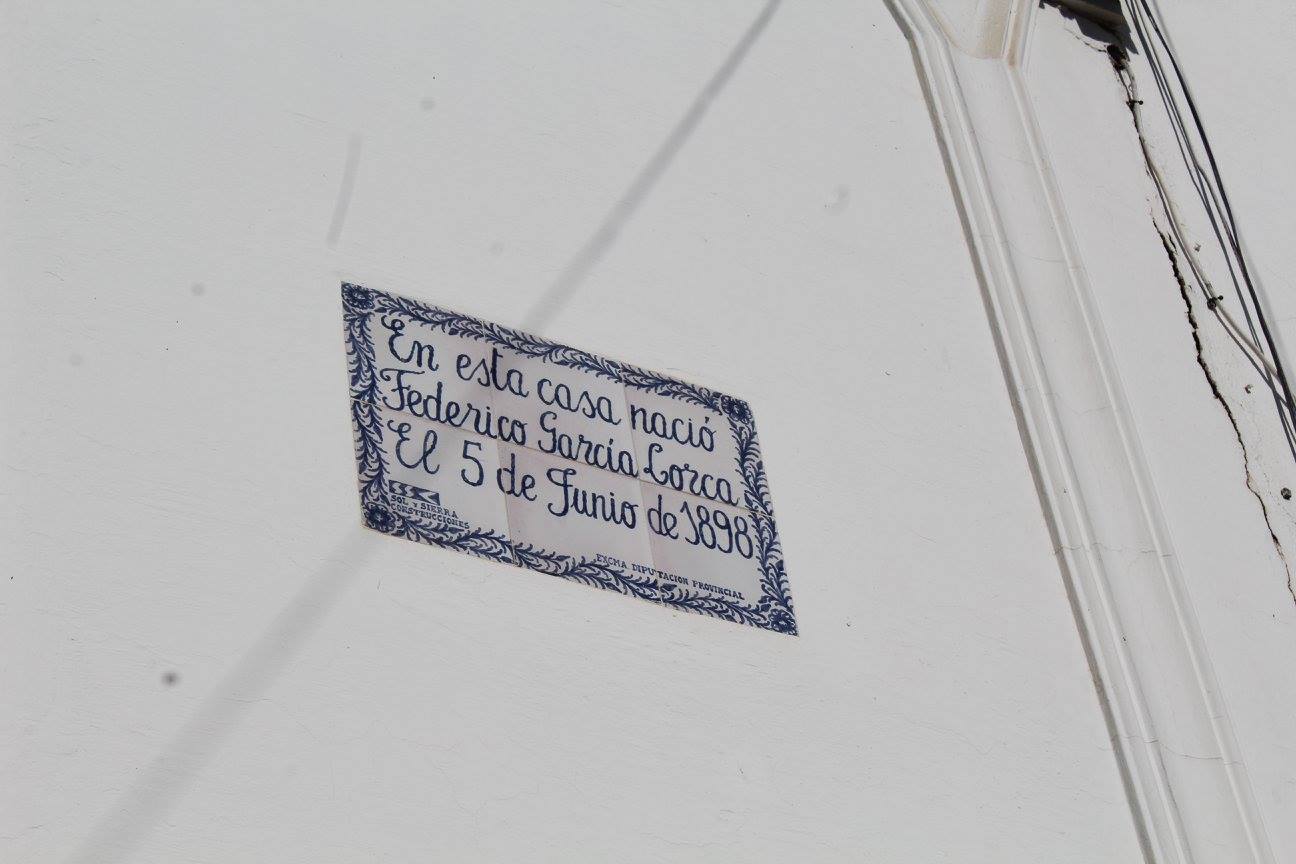

Lorca was born in the pueblo (village) of Fuentevaqueros in 1898. This little sleepy village, nestled in the countryside to the West of Granada is rightfully proud of it’s child, and his birth home has been preserved as a small museum. Lorca’s father, Federico García Rodríguez had sadly lost his first wife, and found his second wife, school teacher Vicenta Lorca Romero in Fuentevaqueros where they settled down.

The house itself is small and modest, though still relatively grand compared to some of the other village houses. You can see all the original furniture including the bed where his mother gave birth to Lorca, and the crib where this famous poet spent his first few years sleeping. For just 1.80, it’s well worth a visit.

Valderrubio (Asquerosa)

Though we had little time left before the Valderrubio house was due to close, we decided to rush over anyway and try our luck. I can’t even begin to explain how happy I am we did, as we had saved the best house for last. The lady in charge was absolutely wonderful and missed her lunch with her mother to keep the place open to show us around. Her passion and dedication to the museum made all the difference to our visit. If you only have time to visit one of the Lorca houses, you have to visit this one. We were fortunate enough to stumble upon the wonderful Pepe during our visit, a local man who was the driving force behind restoring the house and making it into a museum. When the family (who lived here after the Lorcas) passed away, the local council was wondering what to do with the house. Pepe campaigned for the house to be saved as a museum, and then spent the next few years tirelessly searching for all the old furniture (which had been given away to the neighbours when the family moved to the US) and questioning old family friends about every detail of the house in order to return it to it’s original layout. For a long time after he worked for the museum and has since retired. But he made an exception and joyfully showed us around his life’s work, saying in a thick Andaluz accent – ‘te digo cuatro cosillas’…

The Garcia Lorca family moved from the house in Fuentevaqueros to this home in 1905, where they stayed until 1909 when they moved on to a place in Granada. However they kept the house and returned for most of the holidays, including the summers until 1926 when they bought the Huerta. Lorca’s father had inherited a little bit of money from his first wife and he used that money very sensibly, investing it in land to grow tobacco and sugar beet. The latter of which really took off, as following the loss of Spain’s last colonies, they no longer had cheap sugar cane to rely on. They didn’t need to sell the house in Fuentevaqueros when they moved in here, looking for a home with more space for the family and space to store the harvest that was closer to the cortijo where his father managed the land.

This little pueblo was not always called Valderrubio though, it’s original name was Asquerosa, which means ‘disgusting’ in Spanish. Lorca was hugely ashamed of the name of his new hometown, never referring to it by name and just calling it ‘mi pueblo’. He had his friends send his mail care of the nearby village where the post office was situated to avoid telling them the name and he even petitioned to get the town name officially changed to María Cristina (the name of the Spanish Queen). However given the political overtones of the time, the name was rejected and the town remained Asquerosa. Lorca’s friend Salvador Dalí joked that he was the ‘asqueroso of Asquerosa’ which may have exacerbated his hatred for the name as he had a passionate love for Dalí that was never reciprocated. The name Asquerosa did not actually have anything to do with the word disgusting however, as it was originally ‘Ascuruya’, the Nasrid (Muslim Dynasty) name for the nearby river. Later on, long after Lorca’s death, the name was changed to Valderrubio, the valley of ‘tobacco rubio’, as this was one of the first places in Spain to grow it.

Valderrubio has more memories of the Lorca family than just the house – make sure to look out for the Calle Don Federico too. Lorca’s father (a local landowner and producer of sugar beet and tobacco), was a very kind man who gave away all the land on this street to his workers and neighbours so that they could build their own houses on the land. Though Don Federico had no political leanings, he did anger the other landowners of the area for this act of kindness.

Most of the houses in the village either have their own water well, or share a water well with the neighbouring house. This was the case for Lorca’s aunt, Matilde, who also lived in Valderrubio and shared a well with the neighbouring Alba family, run by the matriarch Frasquita Alba. Standing at the well, visiting his cousins and talking to his Aunt, it’s not too hard to imagine where the young Federico got his ideas from for his play ‘The House of Bernarda Alba’! Obviously a few names have been changed and a few details omitted (the real Alba family had sons as well). Needless to say, the Alba family were most put out by his play and never spoke to the Garcia Lorca family again, despite the fact that the two families still share a wall to this day!

Outside the main house, past the large courtyard and the chicken coop and mule stables is the much more modest little home of the lady who looked after the house while the family weren’t there – Maria Mata. It’s just as charming as the big house and filled to the brim with rustic touches and all the original furniture.

Our pilgrimage to the many homes of Federico García Lorca didn’t tell us his whole life story, rather it gave us unique little vignettes into the different places he spent his life, which in a way was more intimate that any other way of getting to know him better. For me, the house at Valderrubio stood out as a truly special visit, and getting to meet the force of nature that is Pepe was an honour and a privilege.

As we drove away from Valderrubio back to the main road to go home to Madrid, we passed an old weathered man, hunched over on his bicycle, one held up leading a perfect example of an Andaluz horse on a short piece of rope. The large black creature trotted alongside, all muscles and glossy coat, while a little scruffy dog ran after them. This is the Spain where time has stood still.

There are so many pueblos in this country which I call home, and each is a box of surprises. Whether you get a famous writer’s family home or witness a fleeting moment of rural life which has disappeared from so many other countries, Spain never lets you down.

March 29, 2016

Hello, I work in Valderrubio House Museum. I read your travelogue; lovely; However you have to change the date in which Federico spent his last summer it was not 1925 it was 1926.

A greeting

Eduardo Ruiz

April 13, 2016

Hi Eduardo,

Thanks for letting me know!

Sarah