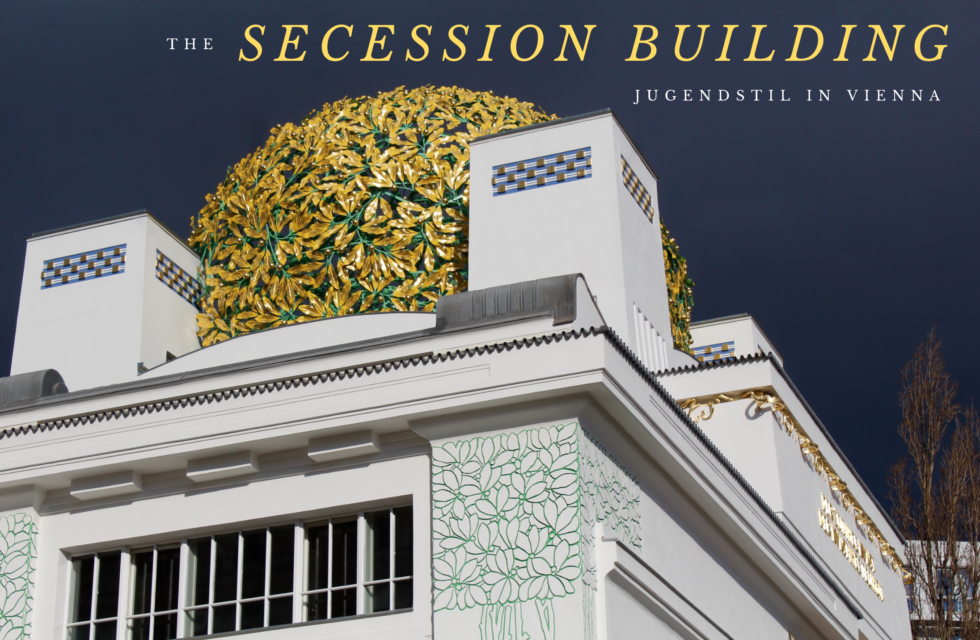

The Secession Building, or Wiener Secessionsgebäude, was built in 1897 as an architectural manifesto for the Vienna Secession. The Secession was a movement of rebel artists who split from the fine art traditions that were the norm of the time.

Ever since I saw a photo of the golden dome on this Art Nouveau, or Jugendstil building, I knew I had to visit. Amid streets of beautiful but traditional architecture, this building stands out like a breath of fresh air, just begging the other, more demure buildings to loathe its shining gold leaf and modern whimsical design.

As you climb the steps and walk through the doors, make sure to look up at the three gorgons that guard the entrance, representing painting, architecture and sculpture. The snakes are playfully entwined, jaws open.

The motto across the building reads: ‘to every age its art and to every art its freedom’, extolling the importance of allowing art to flourish and grow with the times. While ‘modern art’ isn’t everyone’s cup of tea, it is good to see there is space created for it. I didn’t like (or understand) the exhibition that was held there when I visited, but I suppose people thought the same thing about Klimt in his time.

Although as Egon Schiele said: ‘art cannot be modern, art is primordially eternal’.

After looking around the upstairs rooms, head downstairs to the true treasure of the museum in my opinion which my friends described as ‘Klimty’.

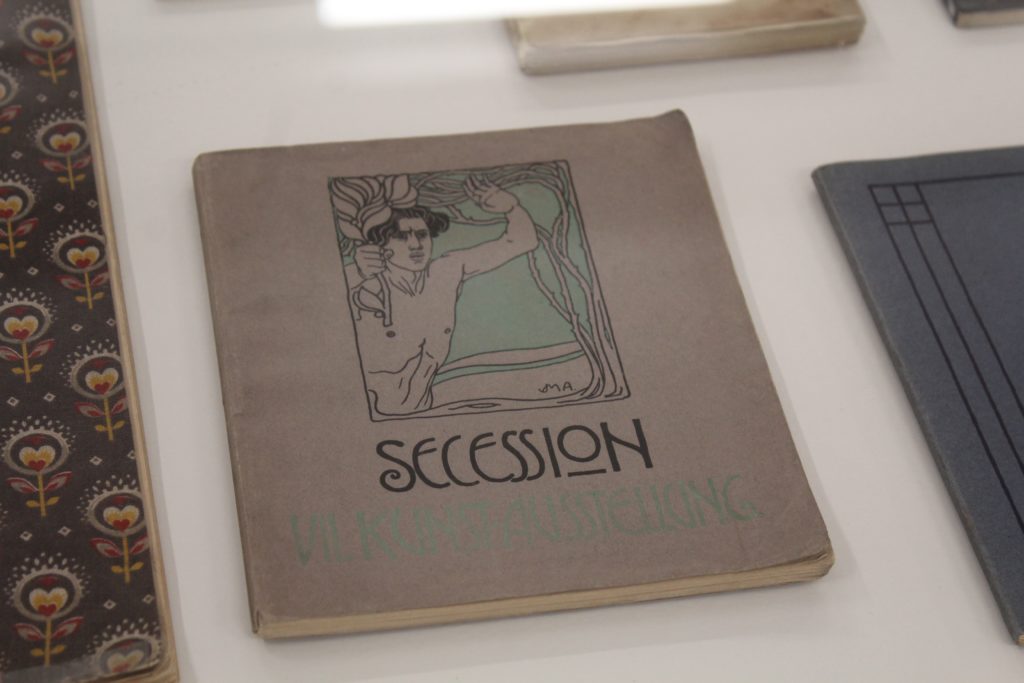

The first room is a little exhibition around the history of the building and the Secession movement which is well worth perusing, but through the next door lies Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze.

It was originally painted in 1901 for an exhibition in the museum and the theme was chosen to celebrate Ludwig van Beethoven. It was painted directly onto the walls and while the painting was preserved after the exhibition, it would not be displayed again to the public until 1986.

The frieze follows the story in Wagner’s interpretation of Beethoven’s 9 Symphony.

It starts with floating Genii, Roman guardian angels, longingly searching the earth for true happiness.

We then come across starving humanity who encounter a shining Knight, and plead to champion their cause. The Knight is fed by Ambition (top left) and Compassion (top right) who ultimately encourage him to set out on behalf of humanity on this Quest.

Along the way he finds the giant monster Typhoeus and his three Gorgon daughters. Alongside them are personifications of Sickness, Madness and Death (to the left), with Lasciouviousness, Intemperanc and Wantonness above to the right.

The brave Knight is able to pass the Hostile Forces and the next panel shows the longing for happiness finding momentary appeasement in Poetry, portrayed as a female figure holding a lyre.

The next panel is blank, as originally this panel was a space in the wall, an opening through which to view Klinger’s life size statue of Beethoven, featured in the original exhibition. My friend said he loved that panel best, and while at the time I mocked him, seeing only emptiness. Now that I know why the panel was blank it makes me think that I should spare blank spaces a second thought as you never know what lies behind them.

The final wall shows the ideal realm, with a choir of Angels singing in paradise and true happiness discovered in ‘pure love’, represented by a kissing couple. This was my favourite panel of course. As an eternal romantic, I’ll always feel that true happiness lies in love. The whole frieze however is truly beautiful, I’m always so moved by Klimt.

Make sure before you leave to go outside and walk around the building. Not only is the architecture worth seeing, but there are pieces of art dotting the outside walls. Look out for the owls by Koloman Moser, a leading artist of the Secession.

February 6, 2019

Beautiful. I’m glad you had a good time. I think you might have enjoyed the Modern Couples exhibition after all – there were some Klimts in that although the focus was on Emilie Folge’s work in the partnership 😉