It’s hard to think about Northern Ireland without thinking of the Troubles. The years of news headlines, car bombs, shootings and images of black balaclavas will haunt the city for many years to come.

The Shankill Mona Lisa – no matter where you stand he’s looking at you, and his gun is pointed right at you!

Not one person I know has travelled to Belfast as a tourist, but the very recent, very troubled history of Northern Ireland should be a reason to visit, not the reverse. There is so much to learn in this city, and so many people desperate to tell their tale. I never mentioned the troubles once when I was out there, yet everyone I talked to somehow brought it up. Despite studying Irish authors of the time, and reading up about the period, there was so much I didn’t know, so much I still don’t.

The fact that Northern Ireland still has segregated education – Catholic schools for Catholics, Protestant schools for Protestants. The fact that there still remain 99 walls, or Peace Lines in Belfast, separating Catholic areas from Protestant and that some of the gates between the areas are closed from 6pm to 6am in Belfast. All the Northern Irish people I met said that the Troubles were a struggle over nationality, not religion – something I’d never considered before.

Some people may say that there’s a big disconnect between the people visiting the city as tourists and the locals walking by their side with painful red scars on their memories. However, I don’t think that’s true. It’s impossible to visit Northern Ireland without feeling some of that pain, and without wanting somehow to help soothe the scars, even when there’s nothing you can do.

The Shankill Road

We took one of the famous Black Taxi Cab political tours of the murals – organised with Paddy Cambell. The tours go around 12pm most days, but it’s best to call up (though not at 9am on a Sunday as you’ll be sure to wake everyone up!) Though the tour was an hour and a half, I felt like I barely scratched the surface of Belfast, and we only really saw the main murals. I would have loved to have spent a day or two wandering around the city, just taking in everything I stumbled across. Next time!

During the Troubles, the Shankill was one of the main centres of loyalist paramilitarism. The Ulster Volunteer Force was founded in the Shankill, and the Shankill Butchers were based in the area too. This gang was notorious for kidnapping and murdering random Catholic civilians – they would torture them then cut their throats with a butcher’s knife, hence the name. They weren’t very careful either, and killed a number of protestants by mistake. Despite receiving the longest combined prison sentences in UK legal history, all of the gang members were released from jail a number of years ago.

The Shankill area is made up of rows of identical cream and brick houses, lined up dutifully on the estates. The area feels pretty bleak, which isn’t helped by the dilapidated surroundings, litter strewn across patches of grass and ever present wire mesh fences which seem to be everywhere. Despite proclaiming that their taxi company is neutral, our taxi driver wouldn’t enter the estate, instead staying close to the car and allowing us to wander around.

One of the most famous loyalist murals is located here (pictured at top), near the Cupar Way wall – the Mona Lisa of Shankill Road. This eerie mural depicts a UFF fighter in a black balaclava, aiming a rifle straight at you. No matter where you stand, to his left, to his right, straight ahead of him, it seems like his eye is fixed on you, and the nozzle of the gun is aiming right for you.

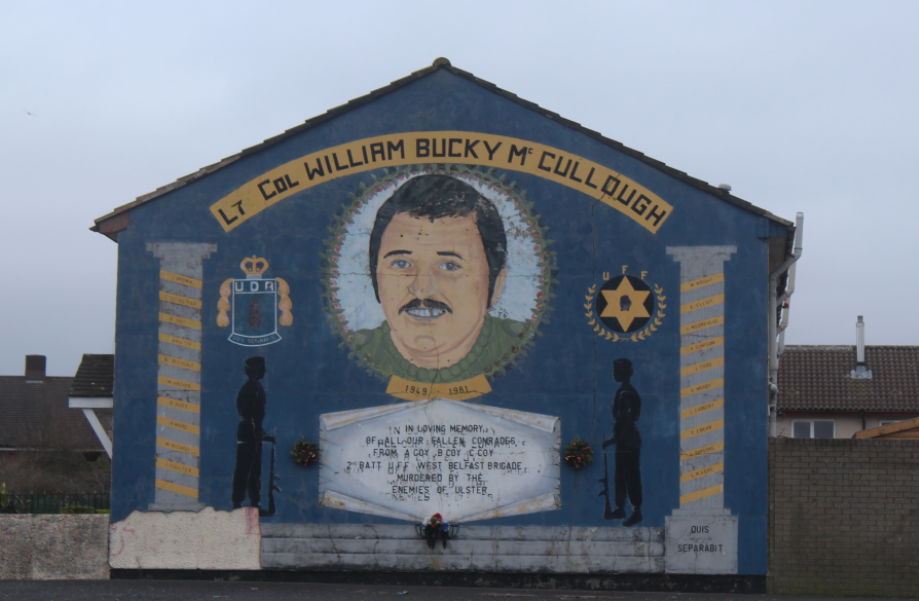

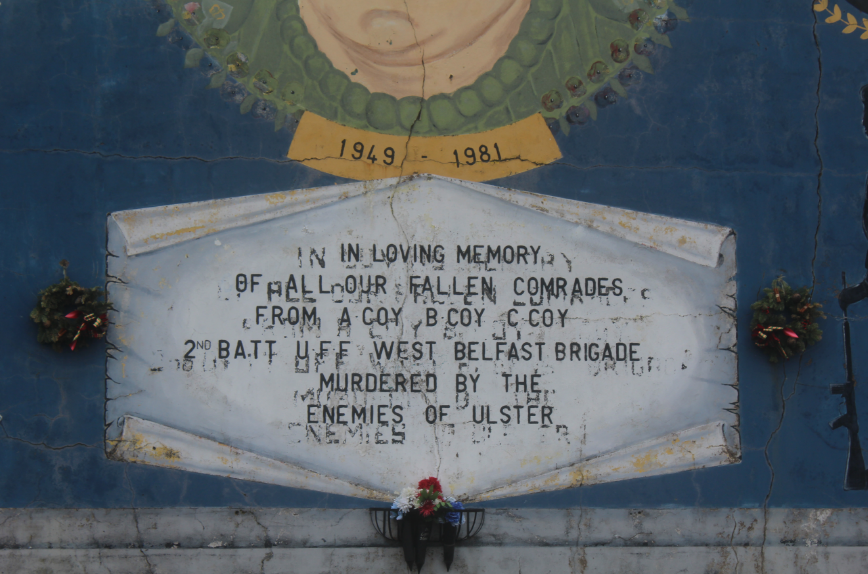

The second most prominent mural (pictured above) is the dedication to Bucky McCullough, a Lieutenant-Colonel (and gunman) with the UDA (Ulster Defence Association) who was betrayed by one of his own. His close friend, James Craig was using money meant for the UDA for his own personal benefit. McCullough started telling people about his activity, demanding an internal enquiry, so Craig decided to have him killed. He passed on information to the republican INLA that he was a leading figure in sectarian killings, and Bucky was murdered in his own home on Denmark Street.

A rough map of the Shankill area

Separating the Shankill and Falls Road areas is one of the most famous walls in Belfast – the Cupar Way Peace Line. The 8m high wall is made of brick and stone, topped with reinforced metal and then finally wire meshing. It has stood for 45 years, 17 years longer than the Berlin Wall. Officially there are around 53 Peace Walls in Northern Ireland, with the majority in Belfast, however a recent study counts the actual number in Belfast at 99 as some of the walls are just wire meshing between houses.

The Peace Walls have been around for almost 3 generations in Belfast, and many live within them, not next to them, as if the boundaries of their worlds end where the walls start. Some people who live on one side of the wall have never met or spoken to people living just 100 yards from them. For all the talk by politicians about the walls coming down, most surveys have shown that the people living near the walls want them to stay. They don’t feel safe without them, and it’s easy to understand why – the young people have only ever lived in their safe shadow. There’s a statistic that almost 90% of the violence that happened during the Troubles happened in the areas near the walls – the walls and gates protect the nearby residents.

Imagine if a giant wall separated one part of Oxford Street from the other half; or if Regent’s Park was split into two, with the gate between allowing free passage only from 9am till 3pm. It’s near impossible. But that exists in Belfast – the gate in the wall separating one half of Alexandra Park from the other half only opened in 2011!

The Clonard Memorial Garden

Across the wall from the Shankill is Bombay Street. You immediately know that you’ve passed into the Catholic area – the tidy lawns are dotted with statues of mother Mary and crucifixes. As we drove past the Church on Sunday morning, elegantly dressed people spilled out, the sound of music echoing faintly from within. Gone were the murals at the end of each row of houses, instead they honour their dead with memorial gardens.

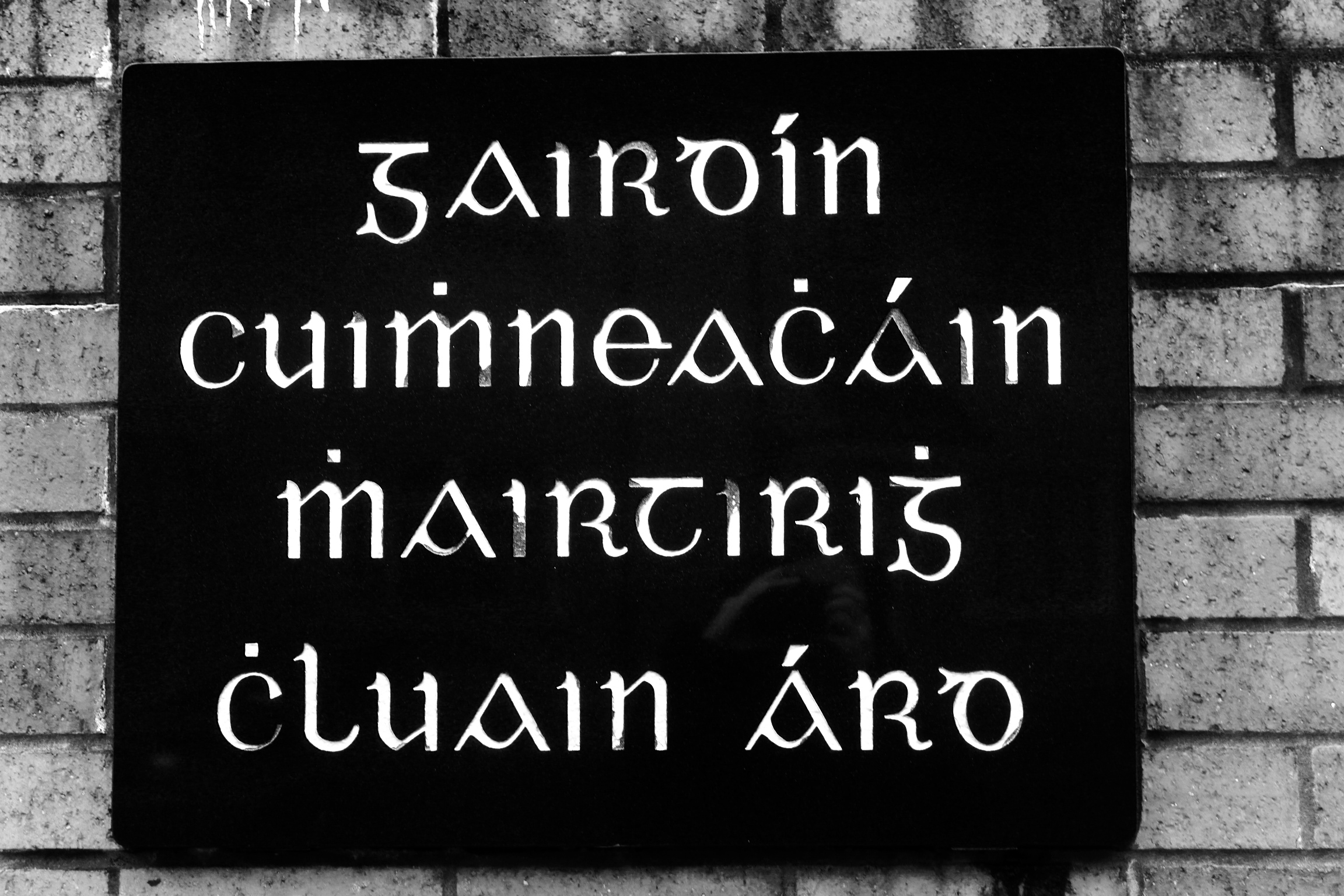

The Clonard Martyrs Memorial Garden is a small corner to the side of the Bombay Street, demarcated by shining black railings and a gate featuring a red phoenix. This is the largest and most elaborate of the Republican gardens in Belfast, commemorating the 25 fallen volunteer IRA fighters and 58 civilians from the area who lost their lives in the conflict. Another plaque pays tribute to the friends of Clonard and ‘the people who have resisted and still resist the occupation of our country.‘ The Irish tricolour flag flies at the back of the garden, a stark symbol of longing for freedom against the corrugated steel wall. Another plaque hopes that the dead people of Clonard ‘be in the midst of Gaelic warriors.’

The desire to be part of Ireland is reflected in the Gaelic language, Celtic crossed and symbols from mythology. Bombay Street witnessed some of the worst of the riots during the Troubles in 1969 when a loyalist mob set fire to all the houses on the street and a shoot out ensued. Despite priests at the Clonard Monastery calling for help, it was only 3 hours later that the British Army finally arrived, but it wasn’t for another few hours that they finally moved to the roads under attack. They called for the loyalists to surrender, but they responded with bullets and petrol bombs. After a bloody fight, they were finally stopped with tear gas. The Phoenix on the gates represents Bombay Street quite literally rising from it’s own ashes.

Falls Road

Further along into the Falls Road area lies the ‘Solidarity Wall’ – a wall featuring murals protesting issues around the world where the nationalists feel solidarity with the people. However the murals that interested me were the ones crying out against some of the horrors of the Troubles. The Falls Road was the scene of the Falls Road Curfew (also known as the Rape of the Lower Falls) from 3-5 July 1970. The British army had moved into the area a while ago to help diffuse fighting between the loyalists and the nationalists and at first they were greeted warmly by the local residents. The Falls Road Curfew however marked the end of the ‘honeymoon’ between the Catholic locals and the British Army. It was considered a terrible strategic move on behalf of the army, and boosted support for the IRA. Following an Orange Order parade in North Belfast, there was heavy rioting in Belfast with both sides blaming the other side for starting the violence. A prolonged gun battle ensued with 7 people dying. In the meantime the IRA organised for a number of weapons to be brought the the Falls Road area to be distributed.

The British army, acting on a tip from an informer, decided to go in and seize weapons from an IRA HQ. After they confiscated 19 weapons, the local youths and IRA volunteered launched a counter attack (throwing stones) to prevent the soldiers from seizing any more weapons, instructing for them to be moved out of the area quickly. The attack quickly escalated and soon hundreds of bullets were flying through the air. The soldiers catapulted canister after canister of tear gas across, which permeated all the houses, the streets and the air. The women and children started evacuating the area. Four hours after the violence started, the soldiers announced via loud speakers that a curfew was being imposed – anyone found on the streets would be instantly arrested. 3000 soldiers moved into the curfew zone and sealed it off with barbed wire. The IRA pulled out quickly at that point, scared of the violence ending badly, and losing their remaining weapons. The British soldiers then started their door to door weapons search of 1000 houses, any journalists on the scene were arrested, perhaps to prevent them from reporting on what they saw:

“The soldiers behaved with a new harshness … axeing down doors, ripping up floorboards, disembowelling chairs, sofas, beds, and smashing the garish plaster statues of the Madonna … which adorned the tiny front parlours“.

After 36 hours, the curfew ended by the arrival of 3000 women and children from the nearby Andersontown nationalist area marching to the Falls Road with supplies of food. At first the soldiers tried to hold them back, but eventually gave up. During the door to door searches, the soldiers confiscated 100 firearms (52 pistols, 35 rifles, 6 machine guns and 14 shotguns), 100 home made grenades, 250 pounds of explosives and 21,000 rounds of ammunition. They were also said to have driven 2 Unionist leaders through the broken and cowed streets – an act that greatly angered the locals.

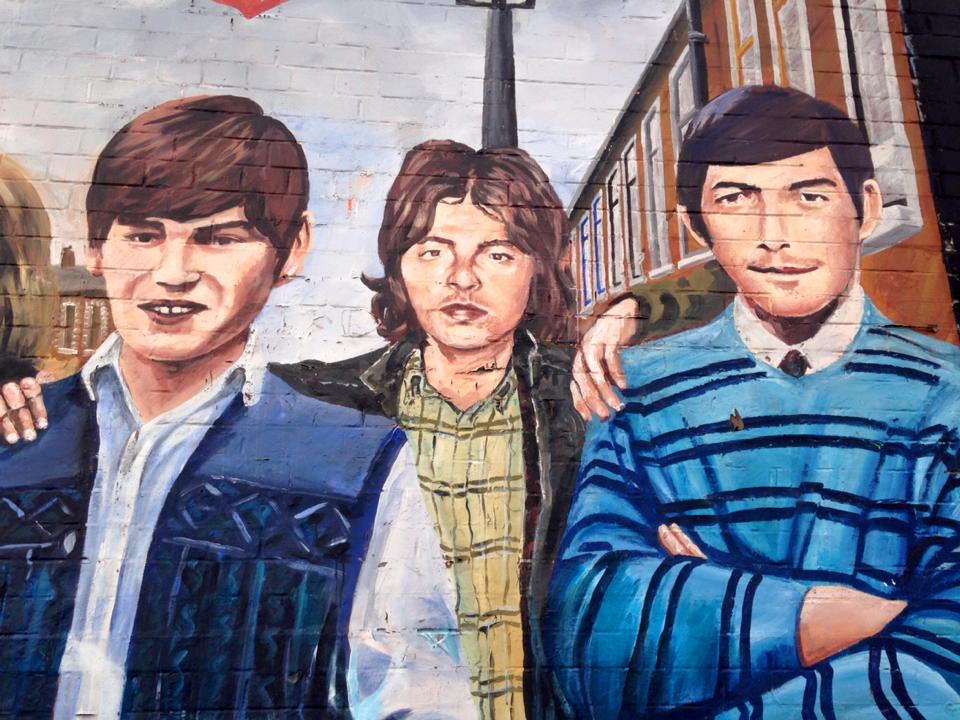

The painting above is a detail from a larger mural, commemorating five local volunteers (Daniel McAreavey, Joseph McKinney, Jimmy Quigley, John Donaghy, Patrick Maguire – Jimmy, JD and Paddy shown above) from the Lower Falls area who died during the Troubles (in 1972). Three died together in an explosion and two were shot, they all died while taking part in some form of resistance. Our Black Taxi driver however told us the story of how these were local youth leaders who were patrolling the streets, ensuring everyone was inside in time for curfew, and were shot down by British snipers stationed on the roof of the Divis Tower. The British army did take the top two floors of the tower block, and a 9 year old child was shot within the tower (the first child to be killed during the Troubles, however it is important to take what your driver says with a pinch of salt. Though Paddy Campbell’s claims to be a neutral taxi company, loyalties run very deep within this divided community.

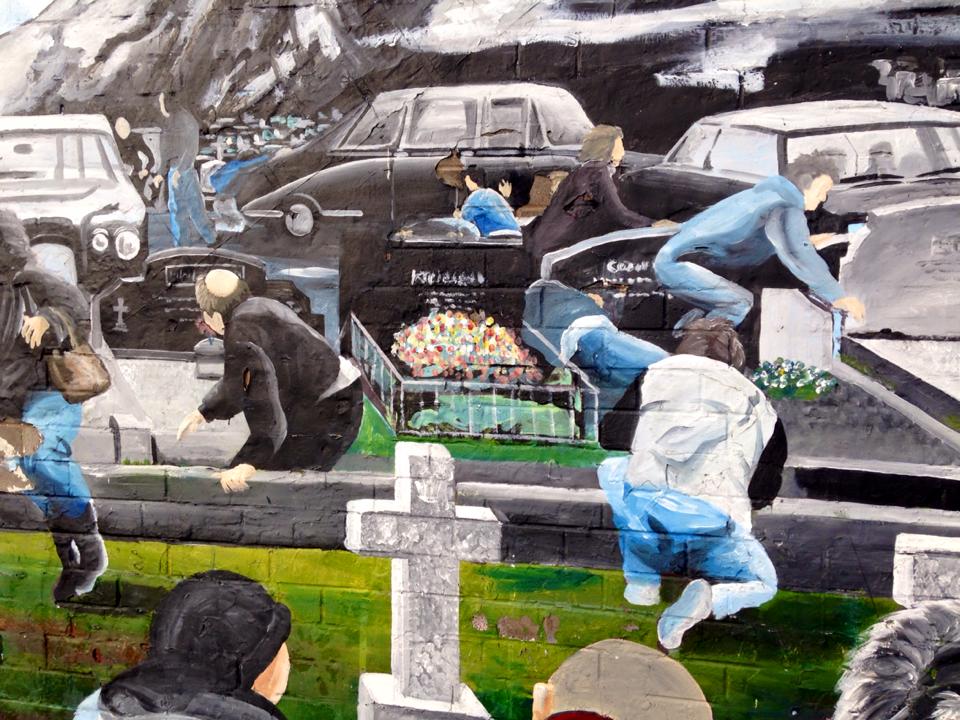

This last mural that was painted to show the horrors of the Troubles depicts a scene at the Milltown Cemetary attack. During the funeral of 3 IRA members in 1988, an Ulster Defence Association volunteer (Stone) attacked the mourners with hand grenades and pistols, killing three and wounding 60. At the funeral of one of Stone’s victims 2 days later, a couple of British soldiers out of uniform drove into the ceremony by mistake. The mourners feared a repeat attack by loyalists, dragged them from the car and they were beaten and eventually shot.

Our black cab mural tour around Belfast felt like the boat ride in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory – when they whizz through a spiralling tunnel of horror and pain, unable to see anything deeper than just a flash of an image here and there. All I can say is I need to go back to Northern Ireland for a longer time to learn more and more. For those with only a weekend though, the Black Cab tours are a must – not only will you get to talk intimately to your local driver but you’ll get to see that proverbial tip of the iceberg which is better than seeing nothing at all!

March 10, 2015

I love reading blogs on my wee country… Even tho I haven’t lived there for sometime now, it’s great to see it all through yours eyes…. Northern Ireland really is a special little country. I hope you get the chance you go back someday and get answers to all the questions you have.

I will be back in September for a month and I can’t wait to walk round Belfast and visit the awesome north coast.

Thank you for taking the time to write about little Norn Iron…

Tom

March 11, 2015

Thanks Tom! I really really loved Northern Ireland – it’s such a beautiful place! Very jealous of you getting to return for a whole month! 🙂 Got lots more to write about Norn still! Have a wonderful day!